16

Venice Architecture Biennale

Water World

Venice. Curious, compelling, labyrinthine, built on the razed forests of Slovenia, Croatia and Montenegro, threaded with canals, sinking, dripping with art, dotted with an embarrassment of architectural riches, overrun with hordes of tourists. It’s a pretty good place to buy a sel e stick. It’s a pretty place for an architecture biennale.

This year, New Zealand has its second-ever exhibition at la Biennale Architettura Venezia, which is often described as the world’s greatest architecture event. It’s hard to argue with the numbers. Over six months, the Biennale will be visited by more than 250,000 people. Sixty-two nations attend and there are 75 separate installations in the wide-ranging exhibition curated by this year’s Pritzker Prize winner Alejandro Aravena, as well as an exceptional retrospective on the drawings and paintings of Zaha Hadid.

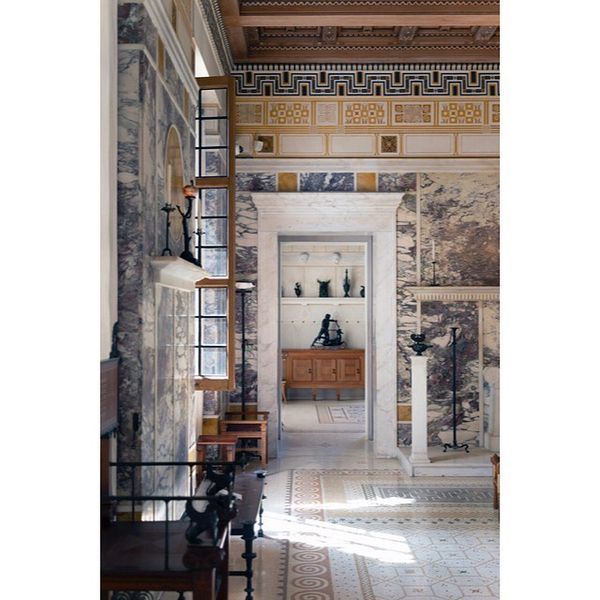

While well-established participants have their own pavilions in the Biennale gardens, the Giardini, relative newcomers like New Zealand nd accommodation elsewhere. This year, New Zealand’s exhibition, Future Islands, is installed in Palazzo Bollani, a restored renaissance building not far from Riva degli Schiavoni, Venice’s well-trodden waterfront promenade. The exhibition announces itself aurally: the delicate strains of waiata that emanate from the stairwell are an enticement upwards. The process of ascending allows a translocation to take place – the Old World of Venice is left behind, a serene new world of oating islands beckons.

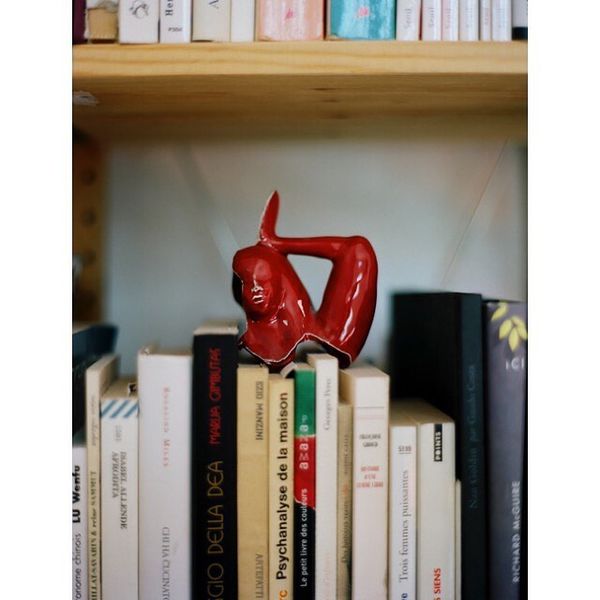

Despite appearing egg-shell delicate, these islands are robust. They’re constructed with the same composite material from which America’s Cup yachts are made, the nautical provenance entirely apt given the island theme. Upon, above and below these islands are exquisitely crafted objects and models, each representing a “proposition about the future”. Some are modest, such as the entrance to Onehunga Primary School designed by Melanie Pau, while others, such as Fearon Hay’s ‘Dune House’, are luxe. There are speculative or unbuilt works that explore potential new worlds for New Zealand architecture, such as a social housing project in Mongolia by Bull O’Sullivan Architects, and there are works – Len Lye Centre, looking at you – that are best described as fantastic. As a collective, these projects show how architects have considered the ways we live, or might live. If there’s another common connection, perhaps it’s that these works, whether built or not, result from atypical briefs.

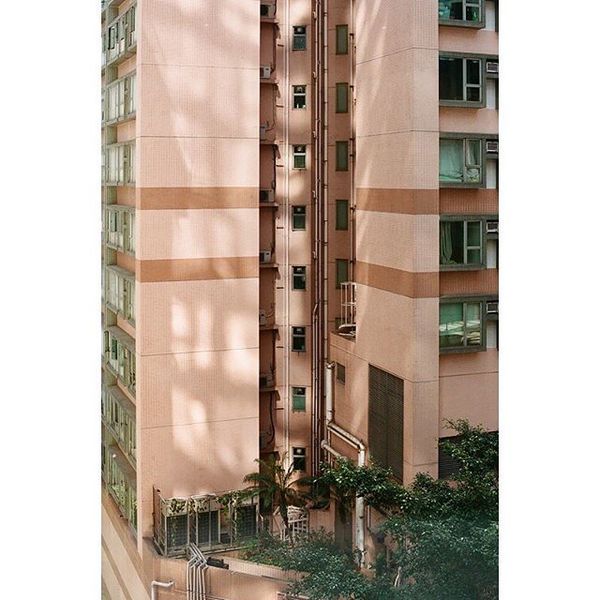

The Biennale typically tends to be about ideas, aspirations and knowledge-sharing, and this year, with Chilean architect Aravena curating the event, this holds especially true. Aravena is known both for epic, monolithic concrete buildings and low-cost ‘incremental’ housing (his ‘half a good house’ schemes provide affordable housing within a framework that allows later extension) but it’s the social aspect of his work that pervades this Biennale. ‘Reporting from the Front’, the Biennale theme, is a call to arms, a request to consider “frontline” world problems – inequality, immigration, sustainability, national identity in the face of globalisation, preservation of community, housing affordability and availability – and how architects are working to ameliorate them.

Aravena says he’s interested in sharing the work of people who are “scrutinising the horizon looking for new elds of action”. His own exhibition, a vast affair situated in Venice’s Corderie dell’Arsenale illustrates this with 75 “success stories where architecture has made, is making or will continue to make a difference”. Some are designed by architects with excellent pedigrees, including Tadao Ando, Peter Zumthor, Wang Shu and Lu Wenyu, and Brit Turner Prize-winners Assemble, but many are by lesser-known practitioners from developing countries. All in all, it’s a dense collection, dotted with high-tech applications of low-tech materials, clever ways of ‘making do’ with what’s at hand. It has been criticised for being too politically correct and for lacking “architecture”, but there are many remarkable stories here that show beauty being invented in the everyday, often for the bene t of the underprivileged.

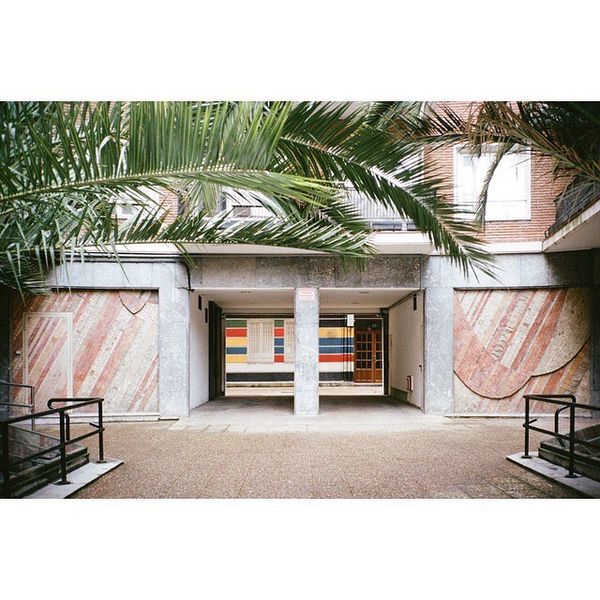

The Biennale’s national participants were also asked to “report from the front”. The preoccupations of many European nations relate to pressing issues of immigration and housing, while the very good, optimistic and accessible Spanish exhibition, Un nished Business, Gold Lion winner for best exhibi- tion, shows how new uses have been found for buildings abandoned during construction during the country’s economic crisis.

Aravena, to illustrate his Biennale theme, uses a photo of German anthropologist Maria Reiche up a ladder in a Peruvian desert seeking new perspectives on Nazca lines, the vast animal shapes etched into the land’s surface. Likewise, Future Islands, in Venice, offers a perspective shift on New Zealand architecture. It is architecture up in the air, poetic, optimistic, a survey of both the realities and possibilities of architecture on these fair isles.

Text Michael Barrett