14

Le Corbusier

Unité d’habitation

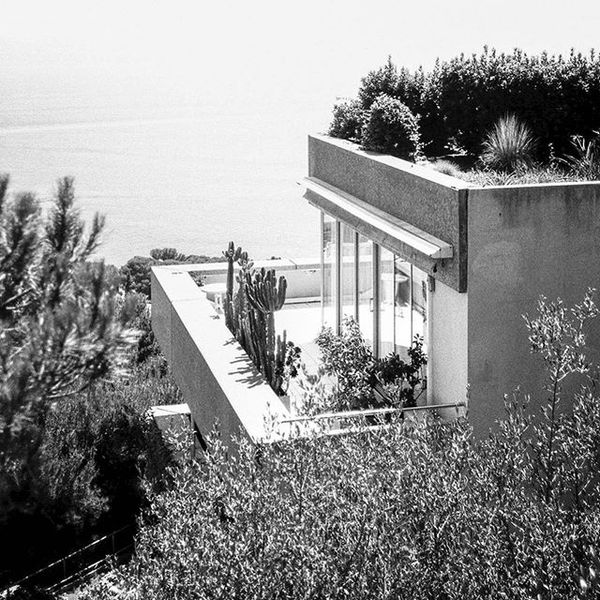

A while ago my partner and I spent three days in one of the 337 apartments in the Unité d’hab- itation in Marseille, designed by Le Corbusier and built between 1947 and 1952. Our petite space had a view towards the Mediterranean from the living room on one side and, from the other, a view of the city stretching out to the rugged limestone hills surrounding Marseille.

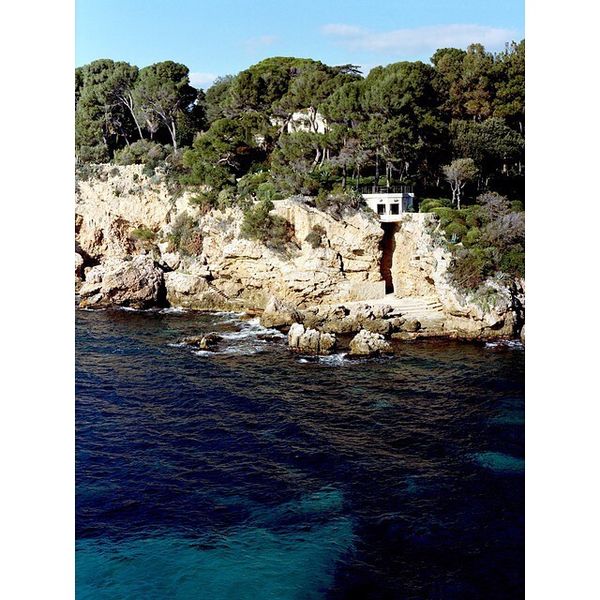

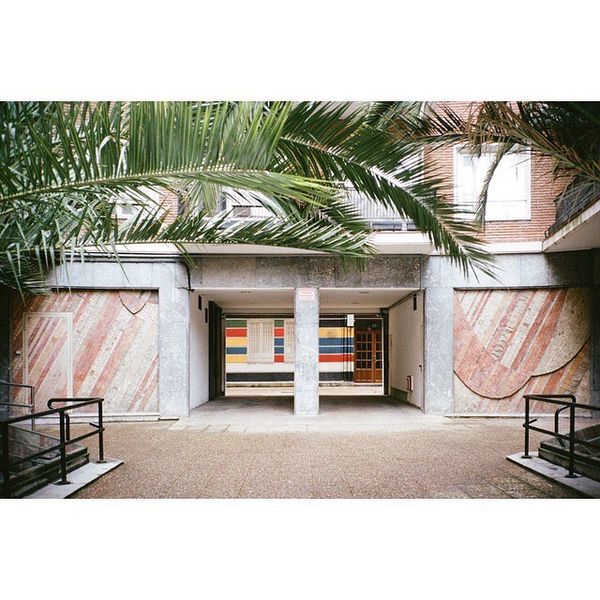

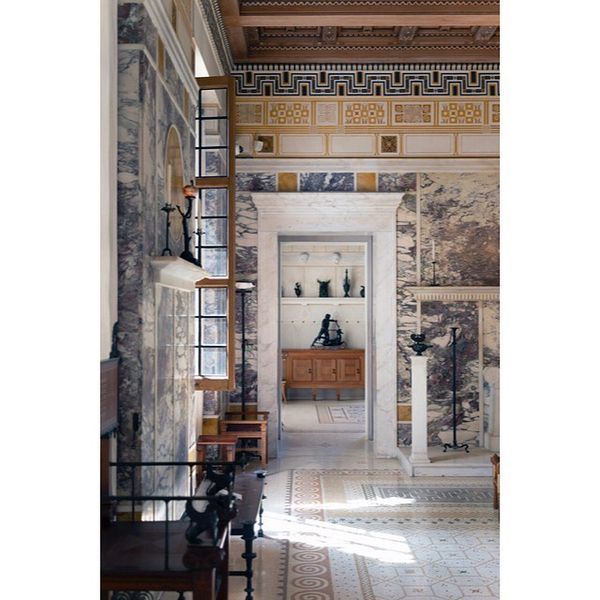

The locals call the Unité d’habitation “La Maison du Fada” (“the crazy guy’s house”). Photos from the early 1950s show a huge, stark concrete building oating like an enormous ocean liner in a sea of French bungalows. This was post-war public housing as idealistic modernism: Built as a prototype, the structure was the expression of an experimental housing solution containing all the facilities required for 1200 people living in a community.

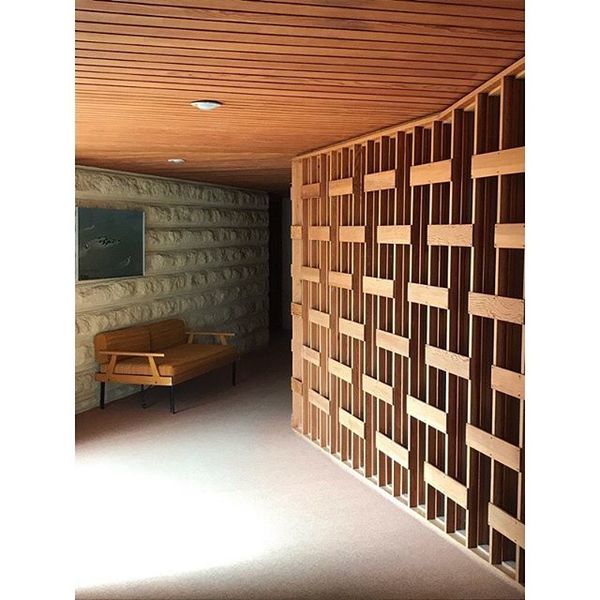

The building contains 23 variations on a basic apartment type, ranging from studio spaces to family dwellings. All of the apartments follow the same concept of a split-level space, with double-height volumes making them feel more spacious than they might. The con guration of our particular apartment meant that as we opened the front door, our view was directed through the dining area and out through the large windows to the sea. The cabin-like kitchen (Le Corbusier likened it to a cockpit) was tucked away to the left and linked to the dining area by means of a serving hatch. Moving into the dining area, you couldn’t help but look down into the living room, where the bed was tucked under the mezzanine. It was a dramatic flourish, generous but at the same time intimate and human in scale.

The apartment’s owner, an architect, had mod- ernised it but retained its original xtures, such as Jean Prouvé’s oak stairs and window frames, and the cast aluminium and tiling of Charlotte Perriand’s kitchen. The balcony, or loggia, was envisaged by Le Corbusier as a space full of plants to bring nature into the apartment, which explains its tiny proportions. It was not meant as a place to linger, but somewhere to smoke a cigarette or drink a coffee while leaning on the concrete bar-like counter.

I mostly just pottered around enjoying the space: eating, reading, watching the changing light and taking photos. My mathematician partner raided the supply of children’s drawing paper to work on some computations, a good sign that he was able to con- centrate in the space. The apartment felt stimulating, but at the same time relaxing and intimate.

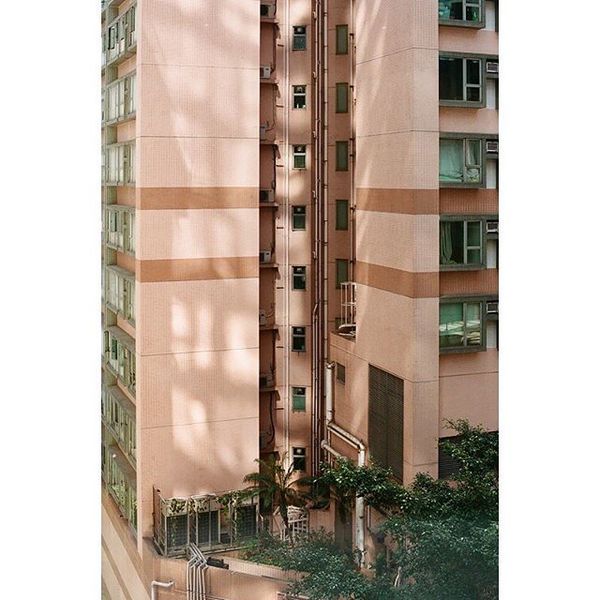

It also made me think about space. On average, Europeans live in around half the living space of New Zealanders. Here in France, where I moved in 2007, apartments are sold by the square metre. My partner and I live in a 65-square-metre apartment, similar in size to the one in the Unité d’Habitation. We have two tiny balconies, one of which is large enough to stretch out a hammock. We have views overlooking a park. Storage space is tight, which means we are constantly editing our stuff. These are good things. It’s not the size of the space that matters, but how you feel when you’re there.